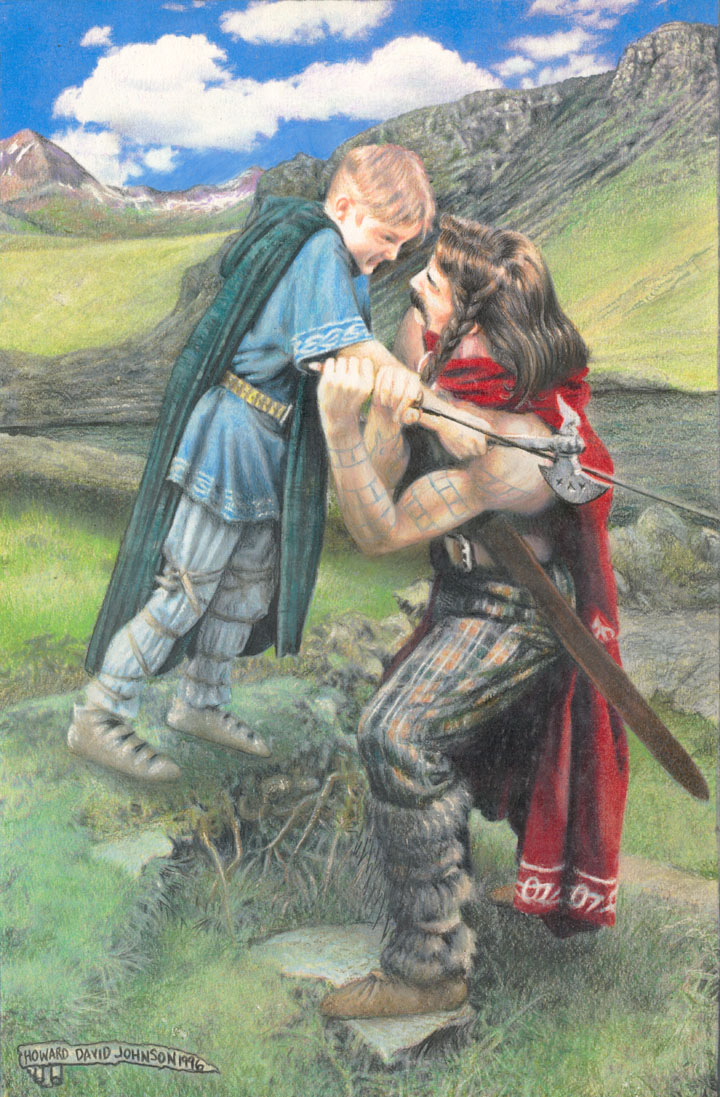

In the Stone and Bronze Ages, Ireland was inhabited by Picts in the north and a people called the Erainn in the south. About the 4th century B.C., tall, red-haired Celts arrived from Gaul or Galicia. A Gaelic civilization was established. By the beginning of the Christian Era, Ireland was divided into five kingdoms—Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, Meath, and Munster. Saint Patrick introduced Christianity in 432, and the country developed into a center of Gaelic and Latin learning. Irish monasteries, the equivalent of universities, attracted intellectuals as well as the pious and sent out missionaries to many parts of Europe and, some believe, to North America.

Norse depredations along the coasts, starting in 795, ended in 1014 with Norse defeat at the Battle of Clontarf by forces under Brian Boru. In the 12th century, the pope gave all of Ireland to the English Crown as a papal fief. In 1171, Henry II of England was acknowledged “Lord of Ireland,” although English control over the whole island was not reasonably absolute until the 17th century. In the Battle of the Boyne (1690), the Catholic King James II and his French supporters were defeated by the Protestant King William III (of Orange). An era of Protestant political and economic supremacy began.

By the Act of Union (1801), Great Britain and Ireland became the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.” Ther was a steady decline in the Irish economy in the next decades. The population had reached 8.25 million when the great potato famine of 1846–1848 took many lives and drove more than 2 million people to immigrate to North America.

In the meantime, anti-British agitation continued along with demands for Irish home rule. The advent of World War I delayed the institution of home rule and resulted in the Easter Rebellion in Dublin (April 24–29, 1916), in which Irish nationalists unsuccessfully attempted to throw off British rule. Guerrilla warfare against British forces followed proclamation of a republic by the rebels in 1919. The Irish Free State was established as a dominion on Dec. 6, 1922, with six northern counties remaining as part of the United Kingdom. A civil war ensued between those supporting the Anglo-Irish Treaty that established the Irish Free State and those repudiating it because it led to the partitioning of the island. The Irish Republican Army (IRA), led by Eamon de Valera, fought against the partition but lost. De Valera joined the government in 1927 and became prime minister in 1932. In 1937 a new constitution changed the nation's name to Éire. Ireland remained neutral in World War II.

In 1948, De Valera was defeated by John A. Costello, who demanded final independence from Britain. The Republic of Ireland was proclaimed on April 18, 1949, and withdrew from the Commonwealth. From the 1960s onward two antagonistic currents dominated Irish politics. One sought to bind the wounds of the rebellion and civil war. The other was the effort of the outlawed Irish Republican Army and more moderate groups to bring Northern Ireland into the republic. The “troubles”—the violence and terrorist acts between Republicans and Unionists in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland—would plague the island for the remainder of the century and beyond.

Under the First Programme for Economic Expansion (1958–1963), economic protection was dismantled and foreign investment encouraged. This prosperity brought profound social and cultural changes to what had been one of the poorest and least technologically advanced countries in Europe. Ireland joined the European Economic Community (now the EU) in 1973. In the 1990 presidential election, Mary Robinson was elected the republic's first woman president. The election of a candidate with socialist and feminist sympathies was regarded as a watershed in Irish political life, reflecting the changes taking place in Irish society. Irish voters approved the Maastricht Treaty, which paved the way for the establishment of the EU, by a large majority in a referendum held in 1992. In 1993, the Irish and British governments signed a joint peace initiative (the Downing Street Declaration), which affirmed Northern Ireland's right to self-determination. A referendum on allowing divorce under certain conditions—hitherto constitutionally forbidden—was narrowly passed in Nov. 1995.

In 1998 hope for a solution to the troubles in Northern Ireland seemed palpable. A landmark settlement, the Good Friday Agreement of April 10, 1998, called for Protestants to share political power with the minority Catholics and gave the Republic of Ireland a voice in the affairs of Northern Ireland. The resounding commitment to the settlement was demonstrated in a dual referendum on May 22: the North approved the accord by a vote of 71% to 29%, and in the Irish Republic 94% favored it. After numerous stops and starts, the new government in Northern Ireland was formed on Dec. 2, 2000, but it has been suspended four times since then (and has remained suspended since Oct. 2002) primarily because of Sinn Fein's reluctance to disarm its military wing, the IRA. In 2005, however, the IRA renounced armed struggle, and peace again seemed possible.

En las Edades de Piedra y Bronce, Irlanda estaba habitada por Picts en el norte y un pueblo llamado Erainn en el sur. Alrededor del siglo IV antes de Cristo, Celtas altos y pelirrojos llegaron de Galicia. Se estableció una civilización Gaélica. Al principio de la Era Cristiana, Irlanda se dividió en 5 reinos (Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, Meath y Munster). San Patricio introdujo el Cristianismo en el 432 y el país se convirtió en un centro de aprendizaje de Gaélico y Latin. Los monasterios irlandeses, equivalentes a las universidades, atrajeron a muchos intelectuales así como a personas piadosas y enviaron misioneros a muchas partes de Europa y algunos creen que a Norte América . Los expolios de los Nórdicos por las costas empezaron en el 795 y terminaron en 1914 con la derrota de los Nórdicos en la Batalla de Clontarf por las fuerzas de Brian Boru.En el siglo XII, el Papa dió toda Irlanda a la Corona inglesa como un feudo papal. En 1171 Enrique II de Inglaterra fue reconocido "Señor de Irlanda", aunque el control inglés de toda la isla no fue razonablemente absoluto hasta el siglo XVII. En la batalla del Boyne ( 1690) el rey católico James II y sus partidarios franceses fueron derrotados por el rey protestante William III (de Orange). Una era de supremacia política y económica protestante comenzó. Con el Acta de Unión (1801) Gran Bretaña e Irlanda se convirtieron en "El Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda". Hubo un continuo descenso en la economia irlandesa en las siguientes decadas. La población había alcanzado los 8.25 millones cuando el "gran hambre de la patata",1846-1848, se cobró muchas vidas y llevó a mas de 2 millones de personas a emigrar a Norte América. Mientras tanto la agitación antibritánica continuaba junto con demandas de un gobierno irlandés. La llegada de la Primera Guerra Mundial demoró la institución de un gobierno local y tuvo como resultado la Rebelión de Pascua en Dublín(Abril 24-29, 1916) en la cual los nacionalistas irlandeses intentaron sin exito deshacerse del gobierno británico. A la guerra de la Guerrilla contra las fuerzas británicas siguió la proclamación de una república por los rebeldes en 1919. El Estado Libre de irlanda se estableció como un dominio el 6 de diciembre de 1922, permaneciendo como parte del Reino Unido 6 condados del Norte. Siguió una guerra civil entre los que apoyaban el tratado Anglo-Irlandés que establecía el Estado Libre de Irlanda y los que lo rechazaban porque daba lugar a la partición de la isla. El Ejército Republicano Irlandés (IRA) liderado por Eamon de Valera luchó contra la partición pero perdió.

.jpg)

.jpg)